https://www.rediff.com/news/column/oh-you-are-kakodkar-president-bush-exclaimed/20191130.htm

'Oh, you are Kakodkar!', President Bush exclaimed

Book Review:

Bridgital Nation By N Chandrasekharan & Roopa

Purushothaman, Penguin Random House 2019

(Appeared in Outlook Magazine.

Towards

a Tata-Birla Plan 2.0

Seventy five years ago on Jan 17, 1944 and on Dec 17, 1944

two slim volumes with far reaching consequences for India were published. They

were titled A Brief memorandum outlining a plan for economic development

of India Part I and A Brief memorandum outlining a plan for

economic development of India, Distribution-Role of the State Part II. The

first was authored by Sir Purushottamdas Thakurdas, J R D Tata, G D Birla, Sir

Ardeshir Dalal, Sir Shri Ram, Kasturbhai Lalbhai, A D Shroff and John Mathai

and the second was authored by the same group except for Sir Ardeshir Dalal,

since in the interim he had been inducted into the Viceroy’s executive council

in charge of planning.

The plan by India’s leading businessmen also came to be

known as “Bombay Plan” perhaps because it was discussed, drafted and finalized

in Bombay, as a matter of fact in “Bombay House”, the headquarters of Tata

Group. It won’t be an exaggeration to say that Bombay Plan which was also

called Tata-Birla plan by the media, guided the course of post war and post-colonial

economy of India from 1947 to 1991.

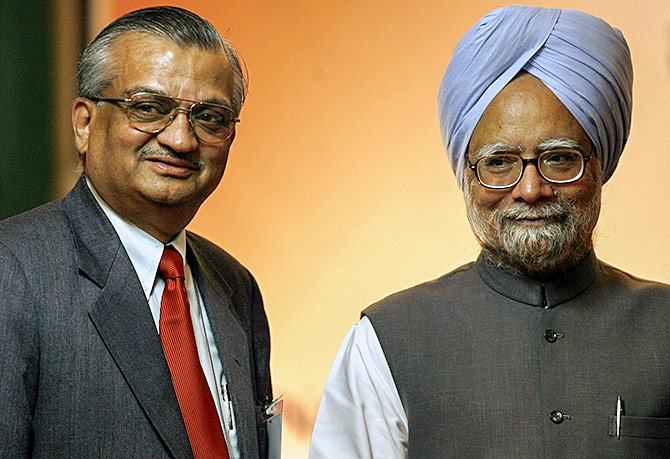

There is no better testimonial to the impact of Tata-Birla

plan than the words of former Prime Minister, Dr Man Mohan Singh, who said

addressing the ASSOCHAM on August 24, 2004 “As a student of economics in the

1950s and later as a practitioner in government, I was greatly impressed by the

"Bombay Plan" of 1944. When we read it today, nearly 60 years later,

we see how relevant many of the central propositions of the Bombay Plan remain.

In those days, it was an unprecedented document. It is worthy of emphasis that nowhere

in the developing world had a group of businessmen come together to draw up

such a long-term plan for a country. The Bombay Plan laid great emphasis on

public investment in social and economic infrastructure, in both rural and

urban areas, it emphasized the importance of agrarian reform and agricultural

research, in setting up educational institutions and a modern financial system.

Above all, it defined the framework for India's transition from agrarian

feudalism to industrial capitalism, but capitalism that is humane, that invests

in the welfare and skills of the working people. In many ways, it

encapsulated what all subsequent Plans have tried to achieve.”

Now everyone is familiar with the big bang reset in India’s

economy from consolidation and protected growth to globalization of markets and

capital that started in 1991. The stirrings for reset had started a decade

earlier. It’s however striking that unlike the captains of industry who

articulated the Bombay Plan, the business leaders of the 90’s and even the

first decade of 21st century failed to articulate their vision for India

in the midst of challenges and opportunities of globalization. Perhaps they

were too busy improving efficiencies, expanding capacities and acquiring assets

abroad. In fact the only document which comes close to a vision document for

that period did not come from business leaders but by an economist who had

served the Indian state in various capacities for decades; Dr Manmohan Singh’s

budget speech of 1991. And that was it.

‘Bridgital Nation’ by N Chandrasekharan who is currently

Chairman of Tata Sons and Roopa Purushothaman, Chief Economist at Tata Group,

is an attempt to provide a vision to guide India in the coming decades of what

they call as the Fourth Industrial Revolution propelled by Artificial

Intelligence and other technological developments. It is slim, about 260 pages

plus notes, well annotated and at the same time captivatingly written there by

making it reader friendly despite the gravitas of the problems they deal with.

They skillfully sketch with colour and brevity the

complexities in the real world of health care; education and skilling; unemployment

and under employment; formal and informal economies; problems faced by women in

the work force; entrepreneurship etc. The authors draw stories, data, lessons from

their own rich experience in services as well as the institutional reach and

memory of Tata Group that encompasses nearly a hundred enterprises that cover

many sectors of the formal economy.

On top of that they have access to over a century of

experience in the vast philanthropy of Tata Trusts and of individual Tata group

companies among literally all sections of society in all corners of India. Among

adivasis; rural communities; remote hill regions, in the heart land and

periphery of the subcontinent; in the areas of education; adult literacy;

health care; self-help groups etc etc. From there they draw rich human interest

stories which act as parables for their theses.

They are able to weave the stories in the grey matter of

ideas, data and graphics. That’s a remarkable achievement stylistically.

At the outset they explain the new word they have coined,

“bridgital”: “we need a new approach that views AI and automation as a human

aid, not a replacement for human intervention. If we do this, automation in

India will look nothing like it does anywhere else. We call this approach

‘Bridgital’.”

There is a visible split in the nature of the Indian

economy—a high-skill, high-productivity sector that produces goods and services

for wealthy, tech-savvy, and urban consumers alongside external markets, and a

low-cost, low-productivity sector that is mostly geared towards the poor. India

is missing a ‘middle’—the midway jobs, the mid-skilled workers.

India’s approach to automation has to be distinct from China,

the US and Japan; it has to focus on technologies that augment and raise

people’s skills.

India does not resemble the traditional story analysts tell

about economic progress. Economic growth does not reflect job growth. While

India is abundant in unskilled and inexpensive labour, GDP growth has instead

been powered by industries that prize skill and capital—scarce resources

unavailable to a vast swathe of the country.

India’s challenges are urgent. It is easy to be trapped in

crisis mode, fighting fires as they spring up. To evolve, though, the country

has to anticipate and actively design the future it wants.

The changes that took place in the early 90’s seem to have

run their course in three decades since, just as the Bombay Plan (1944) had run

its course by the 1980’s. In order to face the challenges of today’s

geo-politics, geo-economics and the explosion in technology, there is a need

for the articulation of another vision document with practical policy

guidelines drafted by India’s best economic, scientific, technological brains

along with business leaders in Manufacturing, Trade, Agriculture, Finance,

Capital Markets and Services.

In the absence of such a vision, we have today in the

corridors of power, an atmosphere of bluster and hubris on the one hand and

groping around in the dark on the other. It can at best be described as a

tactical approach to the challenges rather than strategic.

N Chandrasekharan and Rooopa Purushothaman have ventured to

contribute towards such a new Tata-Birla plan through their book “Bridgital

Nation”. Hopefully it will attract other business and thought leaders to put

aside some time and put in intense effort to articulate a new vision a Tata-

Birla Plan 2.0.

Shivanand Kanavi

(Former VP at

TCS and currently Adjunct Faculty at NIAS, Bengaluru and author of “Sand to

Silicon: The amazing story of digital technology” and “Research by

Design: Innovation and TCS”; skanavi@gmail.com)